Finding the Soul in the Traumatized Body ~ Chris Livanos

“You probably aren’t doing enough yoga.”

“You probably aren’t doing enough yoga.”

Those were the words of the emergency room doctor after my wife somehow managed to hoist me into the back of a car and take me to the hospital after she found me lying on the kitchen floor unable to get up. My chronic back pain had finally reached the tipping point.

Once I started yoga, at age 44, the back problems that had bothered me since my mid-teens went away. So I kept doing it. As long-neglected muscles in my body began to open, my mind began opening to new possibilities and new realities.

I became aware that it was time to seek treatment for the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder that had affected me since a childhood of relentless abuse.

For thirty years, I experienced my body as hostile territory and didn’t even realize it. I had explored many forms of spirituality and meditation, but nothing really clicked for me until I began practicing Hatha Yoga.

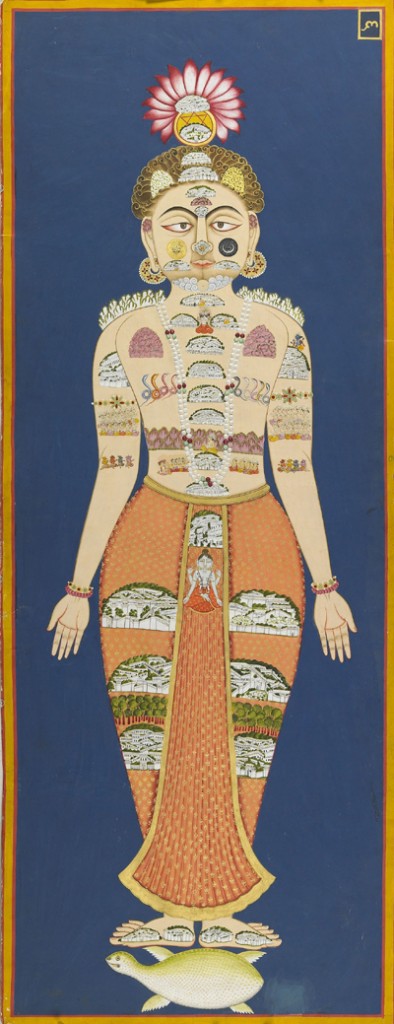

One of the many terms used for the soul in the Bhagavad Gita is dehin, “the embodied one,” and I saw that, for me, the path to the soul would need to lead through the body. If the body is the house of the soul, then as a trauma survivor I’d been living for three decades in a house with the fire alarm activated. That’s what it means to have the sympathetic nervous system in a constant state of hyper-arousal.

Postural yoga has taken off in the modern West because most people live radically out of touch with their bodies, spending more time staring at screens than doing anything that connects the body and the mind as yoga does. Yoga is ideal for people with PTSD, who tend to cope by dissociating–sending the mind to wander off from a body that no longer feels like a safe home. Yoga brings the mind’s awareness to the body, not a body reliving past trauma, but a body experiencing healing movements and postures right here and right now.

I would like to share the gifts of yoga with other people with PTSD and to explore trauma-sensitive yoga, but the yoga that first helped me heal was not specifically directed to trauma survivors and did not need to be. Learning how to move and breathe was all I needed.

I have found that well-meaning attempts by the untrained to be “trauma-sensitive” can be counter-productive or even triggering. When people are doing back-bends or hip-openers, you don’t need to remind them of the emotional nature of the poses. Unless you have the qualifications to deal with the emotional situations that could arise, just cue the pose and trust the power of yoga to let people become aware of their own bodies, minds, and spirits on their own terms.

I was fortunate to have teachers who encouraged me to grow in my own practice without imposing arbitrary alignment rules on me or employing other authoritarian practices that foster dependence and may trigger traumatic memories. My first couple of teachers asked if I was comfortable with hands-on assists, which I was. I appreciated being asked, and I have made a commitment to always ask before giving hands-on assists until I get to know a student. It is a statistical fact that every yoga class has a trauma survivor in it, and my class might be the first environment in which someone experiences being asked for permission before being touched.

Yoga made me aware of my body as God’s most immediate gift to me and the gift that enables me to appreciate all others. I had taught university classes on tantric traditions that use the body as an object of meditation and a vehicle for enlightenment, but for the first time I felt I could begin to understand in a spiritual sense what the saints meant when they spoke of their bodies as temples to worship God and instruments with which to praise him, as when Basavanna exclaimed:

Make of my body the beam of a luteof my head the sounding gourdof my nerves the stringsof my fingers the plucking rods.Clutch me closeand play your thirty-two songsO lord of the meeting rivers!

Chris Livanos is a yoga instructor and a professor of Comparative Literature at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, where he lives with his wife and four dogs.