Yoga: A Warrior’s Practice ~ Chris Kiran Aarya

“As a samurai, I must strengthen my character; as a human being I must perfect my spirit” ~Yamaoka Tesshu, Founder of Shoden Muto-Ryu School of The Sword

If you tell most people that yoga is a warrior’s practice, chances are they’ll try not to laugh since their image of the practice is a room full of women in brightly colored tights stretching and breathing. But dig a little deeper into the roots of what we know as modern yoga and you’ll find a path of discipline, a martial art…a warrior’s practice.

What is a warrior?

A Warrior is one who lives by a warrior ethos. A warrior is not just someone who goes to war and kills people, but rather one who exhibits integrity in their actions and control over their life.

Thus, they live by a code of courage, truthfulness, patience, selflessness, loyalty, fidelity, self-command, respect for elders, love of others, perseverance, cheerfulness in adversity and of course – a sense of humor.

All warrior codes derive from the demanding situations facing a warrior, such as a samurai in a deadly duel. They must perform with the utmost mastery and calm in the face of mortal danger. They must have the ability to reflect and keep their senses in the midst of chaos even when their instinctive and impulsive selves are being drawn out. So in preparation, the warrior hones their body and mind since if they do not, they won’t live for long.

Yoga as a Warrior’s Mental and Spiritual Practice

Among the first mentions of yoga as a warrior’s practice is in the Bhagavad Gita. The Bhagavad Gita is an ancient warrior epic in which Arjuna is being instructed by Krishna to take the warrior code he lives by and slay the enemies inside of himself – to live a life of integrity and to fight for what is right.

“Arise Arjuna, you are a warrior and your dharma (duty) is to fight for a righteous cause…Fight in the spirit of a yogi, your duty calls you.”

A warrior’s training is designed to make them able to overcome fear and the natural survival instinct in the face of danger (against all physical and psychological signals for self preservation). Thus, by channeling a warrior’s dedication and self-mastery – we can also turn inward and face the things our psyche is afraid to deal with.

The first recorded contact between yoga and western thought occurred during the times of Plato (428–348 BCE) and his disciple Aristotle (384–322 BCE). The Greeks had heard much about the Indian yogis, whom they called gymnosophists (naked philosophers) and greatly admired their depth of wisdom.

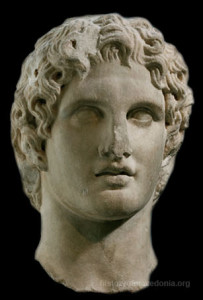

In 327 BCE Alexander the Great invaded a small portion of India, only to abandon it after two years and move back into Persia. Alexander the Great had learned a deep appreciation of philosophy from his teacher Aristotle as well as by Diogenes, and was interested in learning from the yogis. The Greek historian Plutarch tells an interesting story from Alexander’s life that illustrates this interest in yoga.

During Alexander’s invasion of India, his army came upon some yogis sitting in meditation on the banks of the Indus River. Alexander’s column was trying to get through the path but the yogis wouldn’t move.

During Alexander’s invasion of India, his army came upon some yogis sitting in meditation on the banks of the Indus River. Alexander’s column was trying to get through the path but the yogis wouldn’t move.

One of Alexander’s young officers tried to chase them out of the army’s path. When one of the yogis resisted, the officer started yelling at him. Suddenly, Alexander arrived. The officer pointed to Alexander and said to the yogi, “This man has conquered the world! What have you done?” The yogi calmly looked up and replied, “I have conquered the need to conquer the world.”

Upon hearing this, Alexander laughed with approval and admiration. “Could I be any man in the world other than myself,” he said, “I would be this man here.”

What Alexander was recognizing was that the yogi was also a warrior – but an internal warrior. He was so impressed with what he learned over the next few years that he took a few yogis home with him to Greece who became the first teachers of yoga in the West.

Yoga as a Warrior’s Physical Practice

Most of the yoga postures we practice today are a relatively recent creation. While many of the seated meditative postures did originate from ancient Indian texts dating back thousands of years, most of the asanas (poses) we practice today are heavily influenced by 19th and 20th century Indian military and guerilla training.

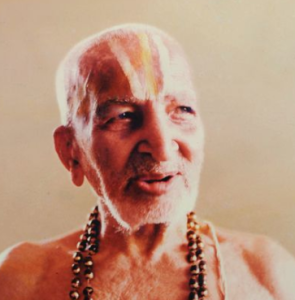

Tirumalai Krishnamacharya is widely regarded as one of the most influential yoga teachers of the 20th century and he is credited with the revival of hatha (physical) yoga after it lied dormant for hundred of years. Most yoga teachers today come from his lineage and for this reason he is often called “The Father of Modern Yoga.”

A strict disciplinarian who was often compared to a drill sergeant, Krishnamacharya even referred to his own teacher Ramamohana Brahmachari as “sergeant” in the first edition of his book Yoga Makaranda.

The vinyasa yoga system that Krishnamacharya created and taught in the early 20th century drew on hatha yoga, as well as traditional Indian wrestling and gymnastics, British Army calisthenics and, according to the scholar Mark Singleton, Danish educator Niels Bukh’s “primitive gymnastics.” These practices included sun salutations and standing poses, such as the triangle pose, which did not appear in any ancient yoga text.

And many of the practices Krishnamacharya drew on to create modern yoga were described by Singleton as practices used by Indian guerrilla warriors: “…exercise regimes designed to inure their bodies to the harsh physical conditions of the itinerant life and to prepare them for combat.”

And many of the practices Krishnamacharya drew on to create modern yoga were described by Singleton as practices used by Indian guerrilla warriors: “…exercise regimes designed to inure their bodies to the harsh physical conditions of the itinerant life and to prepare them for combat.”

During the time of resistance to British rule in India, saying you were “doing yoga” was according to Singleton, covert language to describe warrior training:

“To “do yoga” or to be a yogi in this sense meant to train oneself as a guerilla, using whichever martial and body-strengthening techniques were to hand.”

This is also why hatha yoga is seen by many as a martial art.

Yoga as a Warrior’s Practice

In combining the physical, mental, and spiritual aspects of yoga into a warrior’s practice, a clearer path begins to appear. In not only living by the warrior code but also turning it inward with integrity, we see a path of discipline and self-improvement to better serve our families and friends, our communities, and ourselves.

And note that adhering to this practice is not incompatible with being a good Christian, Muslim, Buddhist, or Atheist but rather it can help make you better at whatever path you’ve already chosen.

In addition to the physical practice of asana and pranayama, here is more of what our inward journey focuses on:

Focus: Developing the ability to bring impeccable attention inwardly and outwardly, to focus on the task at hand and to not turn away from the unpleasant truth but to look it in the eye.

Living Your Duty (Dharma): what are you practicing for?

Self Knowledge: Radical honesty about the light and dark sides of who we are.

Converting Fear to Discernment: Fear is not a disease but an invitation to discernment. As Carlos Castaneda said in Don Juan: “A necessity of a warrior’s life is the need to experience and evaluate the sensation of fear.”

And with yoga as a warrior’s practice, we learn to convert fear into discernment. We do so by venturing into the unknown facets of the world and ourselves to explore, test ourselves, hunt for meaning, and learn from the experience.

This can be done by climbing a mountain, trying a new yoga pose, or trying for a new personal record in the clean and jerk. Though facing fear, we gain power that manifests itself as clarity of thought and decisiveness of action. If we don’t face the unknown on a regular basis, we can’t really grow and improve.

Self Discipline/Sadhana: A rigorous moral and physical practice to live the virtues of the warrior code and cultivate our ability to have impeccable attention, convert fear to discernment, accept responsibility, and take a daily accounting of our actions and intentions.

Accepting Responsibility For our Actions and Intentions: Having the courage and fortitude to accept responsibility for our actions and intentions which can be a challenge since our ego will try to give us every reason or excuse to not to do so. But in doing so the ego is serving one purpose, to keep you dependent on an externally-derived self-image. A warrior’s self-image is internally, not externally derived.

As we accept responsibility for our actions and intentions, we also accept a simple truth; life is difficult. Once we fully accept difficulty as natural and normal, we are no longer daunted when we encounter a struggle or a test.

Instead, we embrace these tests as opportunities. Difficult experiences are the way we learn, and are they are also the way we can appreciate ease. By embracing these experiences, we allow ourselves to find peace within our difficulties rather than wasting our energy trying to escape them.

This is the way of the Yogi and the Warrior.

About the author. Chris Kiran Aarya, E-RYT 500, is a 22-year Army veteran who served in Iraq and has been studying yoga for over 30 years and teaching for twelve. Together with his wife Maya Devi Georg, he runs the Brahmaloka Yoga School. A dedicated yoga practitioner and teacher (who first learned yoga at the age of seven), he combines three decades of practice along with over two decades of group fitness and outdoor leadership experience into his teaching and he enjoys helping students break through to new levels of ability and self-belief.

About the author. Chris Kiran Aarya, E-RYT 500, is a 22-year Army veteran who served in Iraq and has been studying yoga for over 30 years and teaching for twelve. Together with his wife Maya Devi Georg, he runs the Brahmaloka Yoga School. A dedicated yoga practitioner and teacher (who first learned yoga at the age of seven), he combines three decades of practice along with over two decades of group fitness and outdoor leadership experience into his teaching and he enjoys helping students break through to new levels of ability and self-belief.

Chris trained with Doug Swenson and his multi-faceted vinyasa style of yoga; Sadhana Yoga Chi and his teachers and influences also include Yogini Shambhavi, Meta Hirschl, David Swenson, and Tias Little.

Chris currently teaches workshops, teacher trainings, and yoga festivals around the US and Europe. He has written for or appeared in Mantra Magazine (USA), Origin Magazine (USA), ΥogaWorld (Greece), Yoga Nova (France), Elephant Journal (USA), Brahmaloka or Bust, LA Yoga (USA), ABC Joga (Poland) Flow Yoga Magazine (USA), Integral Yoga Magazine (USA), Yoga Journal Online (USA), and Politico (USA) and his work has been translated into German, Polish, Greek, French, Italian, and Spanish